by Laura Parker Roerden

It came to my attention recently that I had just hit an anniversary: 25 years of scuba diving. We are also today celebrating 50 years since the first Earth Day celebration.I don’t know how all that has passed so quickly, but something about these particular anniversaries has me deeply nostalgic for the seas I first knew a quarter century ago.

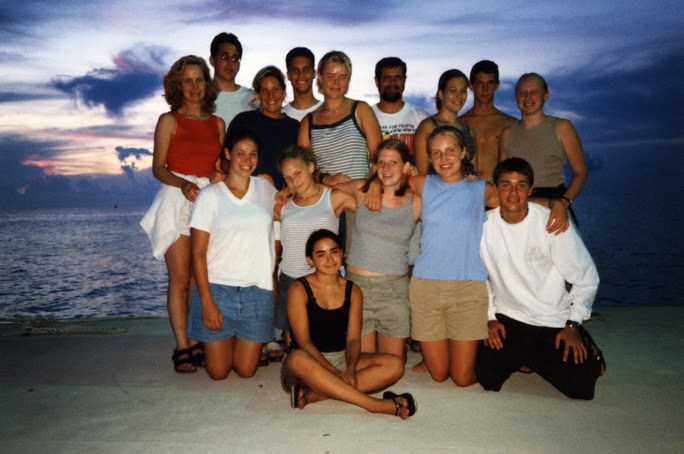

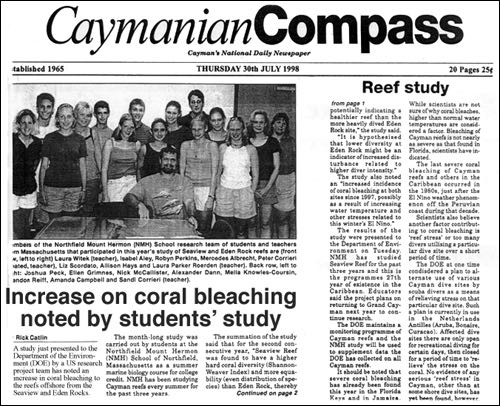

My first summer as a diver in the early 1990s, I was the head marine biology teacher in a summer school’s five week marine biology course in Grand Cayman, BWI (an early incarnation of Ocean Matters). I headed to Grand Cayman with my newly minted dive certification, filled with plans and expectations for a grand adventure on the coral reef. The reef did not disappoint. Together with a scuba instruction team and my assistant marine biology teacher Chris Gawle, we designed a course for twenty school students, doing a benthic survey on scuba of two sites with differing dive pressures to look at algal and coral diversity as indicators of health. We dove twice daily on the reef.

We spent mornings underwater hovered over quadrats identifying and counting algae and coral species for our research project. In the afternoons, we simply dove on the reef. We became familiar with its nooks and crannies: waved ‘hello’ to the resident queen angelfish as we swam by; stopped at a favorite coral head to see the moray eel; marveled at the simple interdependency of a tiger grouper having algae cleaned from its mouth by a team of gobbies and a wrasse.

We’d kick our way out to Eden Rock, a wonderland of dense coral heads that grew together in a maze of swim-throughs, where schools of thousands of tiny silversides moved in unison and reflected the light in angular moves like a living mosaic. Impossibly large fish would show up—Goliath groupers each the size of a grown man— and swim by our sides, a giant and dis-interested fish eye trained at our bubbles.

We knew which of the finger-like channels that ran perpendicular to shore to navigate to the wall, the sheer vertical drop that begins at 70 feet and plummets until it reaches the continental shelf at twenty-five thousand feet. On the wall, we’d hover over the dark abyss at 90 feet, where light from the surface supported an abundance of marine life: bright red corkscrew sponges, thick like rope; a delicate purple vase sponge frozen in the pose of falling from a small ledge; hundreds of tiny blue chromis, tiny jewel-toned fish shimmered like a Chagall window.

Marine scientists whom we worked with at the time at the Grand Cayman Department of the Environment were concerned about global warming and predictions were that we’d lose more than half of our reefs by 2020 from the combined effects of man-made stressors such as warming water and pollution. I returned home and told my friends what was at stake. One said, “Why aren’t we hearing about this in the U.S.?” Shortly after, a new book called Earth in a Balance by Al Gore was published.

Twenty-five years later, as we approach 2020, we are already closing in on that prediction of coral reef loss and tragically on target to outpace it. Normal coral cover in the Caribbean in the early 1990s when we began our research project was 20-25%; now it is as low as 10%. Ocean Matters students were recording its slow decline year after year. 60-70% of fish stocks are officially considered to have been fished to their limits over overfished. The grouper once so plentiful on the reef 25 years ago, is now listed as threatened, with populations declining by 60% in a few decades. Warming waters, destruction of habitat, plastic and nitrite pollution, ocean acidification are all effects that have added up and led to the decline of the health of our world’s oceans.

What does this all mean for us? Many people assume scientists and environmentalists must be exaggerating the decline of the ocean. It’s been 25 years and our lives are still relatively recognizable. Sure, we’ve had some bad storms here and there and some tragic wildfires out west, but we still can find fish like Cod and shrimp at most grocery stores or restaurants in America.

What we might not realize, however, is how tenuous that supply of fish has become. The Cod fishery, once plentiful off of Massachusetts in the once aptly-named Cape Cod Bay, collapsed by more than 95% in the late 1990s and despite closing fisheries has yet to recover. We now depend on Cod from much further northern waters, increasing the carbon footprint of each gram of protein we consume. It’s as if the Cod is retreating from us like sheets of ice on the poles. The story of shrimp is no more encouraging. A single wild-caught shrimp carries with it six pounds of by-catch, thrown back into the ocean dead. A plateful of shrimp carries with it a grotesque amount of waste.

While these facts swirl around in my conscience, it’s the beauty of the reef that I knew in my youth and the sense of it slipping away like sand through an hour glass that haunts me. To not act to protect it would be like knowing that a school bus full of children is careening off a cliff. Surely, we would do something to stop it.

The tiny gears that drive the engine of life in the ocean also dive the gears of all life on this watery planet. They drive our weather, create the oxygen in our atmosphere, supply the world with protein, buffer the impact of storms in our communities. The ocean is the BIG IDEA to which our human health is connected. It’s both our grocery store and our life support system. What we do to the ocean we do to ourselves.

Years of working with teenagers who are literally submerged on scuba in the ocean, however, has me also understanding that the impact of our wild places is deeper than just the environmental services they provide. Our relationship with nature teaches us about ourselves, helps our children find places where they can belong, shores up our families and communities, and widens the concept of our tribe.

Young people’s hearts reflect what they see and experience. When they have time to explore wild places that have integrity—they will reflect that integrity in their actions.

So while we talk a lot about saving our ocean and our wild places, really it’s the other way around:

Our wild places save us.

I’d like to end by sharing this offering from native New Zealand: the Haka, a dance performed in tribute to our “belonging places” and the wish that we all find our belonging places on this watery planet and the spaces in our heart where they inhabit.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EgU-RWQ4J7o

Laura Parker Roerden is the founder and executive director of Ocean Matters and the former managing editor of Educators for Social Responsibility and New Designs for Youth Development. She serves on the boards of Women Working for Oceans (W20) and Earth, Ltd. and is a member of the Pleiades Network of Women in Sustainability.

One thought on “Earth Day, Anniversaries and Our Belonging Places”

Comments are closed.