by Laura Parker Roerden

Ocean Matters high school-aged volunteers will be lending a hand this March 2019 at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in creating and ground-truthing a color coded key for researchers to more accurately assess levels of health of Hawaiian coral species. This first ever Hawaiian color key will replace one developed in Australia for tracking health there, which has been found to be less than accurate when applied to Hawaiian coral species, but to be a very useful tool for assessing health in corals in general.

Why is this important?

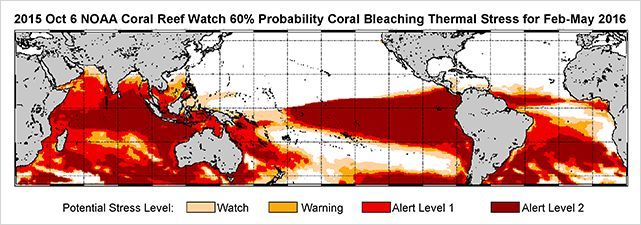

This summer massive coral bleaching is anticipated in the Hawaiian islands as a result of higher than nomal water temperatures from global warming. Corals that have been bleached are less likely to survive if other chronic stressors are also present. As bleaching events become more common across the globe, it’s important to be monitoring the status of reefs, in part to better understand the mechanisms of loss and recovery, as some corals show better resilience or recovery than others.

What is coral bleaching?

Ask anyone who has visited the coral reef about her experience and she is likely to paint a colorful picture of soft pinks, mauves, purples, greys and browns, an abundance of diversity and life thriving in crystal clear waters with fingers of sunlight reaching to the depths in excess of a hundred feet. Waters in the tropics are clear, unlike cold water, because they do not have nutrients in them. So how in fact does all that life get supported in a virtual desert of nutrient poor water?

Sunlight driving a symbiotic relationship of zooxanthellae algae in the coral animal is the short answer. The algae living within the tissue of the coral animal delivers coral a way to convert sunlight into energy. The corals also get their colorization from the pigment of the algae. When we hear about coral bleaching, researchers are referring to warming waters causing the algae to jump ship from the coral animal, leaving the coral without energy (and color), making them vulnerable to mortality. By assessing the different colors and change over time, researchers can tell a lot about both the symbiont living within and the level of stress the coral animal is under.

How common is coral bleaching?

Coral bleaching only began in the 1980s, when effects from warming waters began to impact reefs globally. Until recently, the Hawaiian Islands had escaped widespread bleaching events where high mortality of corals occurred. However, in 2014 and 2015, Hawai‘i experienced unprecedented widespread bleaching and mortality. Most islands reported well over half of the corals exhibiting signs of paling and bleaching and subsequent death. The continued increase in global temperature due to anthropogenic production of CO2 from fossil fuels and other human induced emissions means that future bleaching events will be increasingly more severe and frequent.

How does the color key work?

HIMB is currently conducting laboratory trials with different species of corals. By increasing temperatures slowly and taking samples of each colony as the colors change, they can create a key linking color to health.

To understand what is happening to the corals physiologically as they bleach, researchers take pulse-amplitude modulation (PAM) measurements. From each fragment they extract and measure the chlorophyll a content using a spectrophotometer, which measures the reflectance or transmittance at a certain wavelength. This will tell us the concentration chlorophyll as it relates to color.

They are also counting the hundreds of zooxanthellae (the tiny single celled algae that have a symbiotic relationship with the corals) that provide color in corals and are reduced as bleaching progresses. Originally developed to count blood cells we use a hemocytometer to determine the symbiont densities in coral. This will give us a link from cell counts to color.

We are grateful to the young people for giving up their time for this important effort and to our hosts at the Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology for their support of the young people. A special shout out of gratitude goes to Alaska Airlines for their special group airfare for this project.

Laura Parker Roerden is the founder and executive director of Ocean Matters and the former managing editor of Educators for Social Responsibility and New Designs for Youth Development. She serves on the boards of Women Working for Oceans (W20) and Earth, Ltd. and is a member of the Pleiades Network of Women in Sustainability.

Laura Parker Roerden is the founder and executive director of Ocean Matters and the former managing editor of Educators for Social Responsibility and New Designs for Youth Development. She serves on the boards of Women Working for Oceans (W20) and Earth, Ltd. and is a member of the Pleiades Network of Women in Sustainability.